Is going to a hair salon still relevant—for men, for boys, for anyone at all? In an age of trimmers, mirrors, online tutorials, and the quiet confidence of self-maintenance, is the periodic haircut still a marker of civilised life? Or is it merely one of those habits we carry forward unquestioned, like shaking hands or standing in queues? These thoughts hovered loosely in my mind on a cold morning as four of us set out together for a haircut.

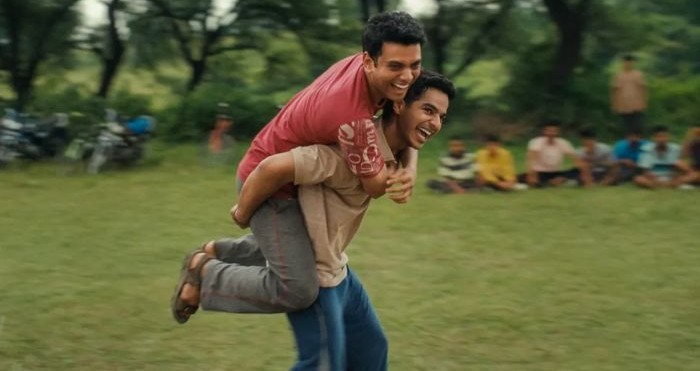

We made an unlikely little procession through Millburn city center: myself at seventy-three, my son at forty-five, and my two grandsons—handsome, energetic, and faintly suspicious—aged nine and six. Three generations, four heads of hair, and one shared destination: Super Cuts.

For the boys, the outing required persuasion. A haircut, to them, is a mild imposition inflicted by adults who seem to possess an exaggerated fear of untidiness. Negotiations began almost immediately—how much hair would be sacrificed, whether the fringe could be spared, and why hair that was growing quite happily needed intervention at all. Their objections were earnest, their resistance polite but unmistakable.

My son approached the visit with calm efficiency. Haircuts belong, for him, to the category of routine maintenance—like renewing subscriptions or replacing batteries. Necessary, sensible, and best completed without emotional investment. The outcome was already accepted; only the duration remained uncertain.

Watching them, I was carried back to my own childhood, when haircuts arrived not by appointment but by visit. The barber then was something between a professional and a family institution, much like the family doctor. Once a month, he would appear at our home, his tools wrapped carefully in cloth, carrying with him an air of quiet authority. One by one, my brothers and I would be summoned and seated on an old chair, a large cover cloth tied around our necks. We despised the proceedings uniformly. The instruments—strange looking scissors, sharp-edged razors—were objects of mild terror, and the sound they made too close to our ears tested a bravery we did not entirely possess. Our father watched from a distance, saying little, his presence alone ensuring compliance. Resistance, we knew, was futile.

Years later, when my own son was young, the setting changed but the spirit endured. The barbershop had become a place of conversation as much as grooming. Opinions were exchanged freely—on cricket, politics, prices, and prospects—often with greater confidence than accuracy. The haircut unfolded amid laughter and argument, the scissors keeping time with talk. And again, the father’s presence mattered. He sat nearby, observant, approving, occasionally intervening but largely silently endorsing the ritual being passed along.

Super Cuts, today, is a different world altogether. Clean, bright, efficient—and notably hushed. Conversation is minimal, almost optional. Names are replaced by numbers. The only sounds are the subdued clipping of scissors and the muted whirring of trimmers. The ritual has been streamlined, its social excesses neatly trimmed away.

And yet, as the boys settled—uneasily—into their chairs, I realised that something essential remained unchanged. Each generation approached the moment differently. The six-year-old sat stiffly, eyes wide, as though courage itself might keep the scissors at bay. The nine-year-old attempted sophistication, issuing carefully rehearsed instructions. My son surrendered quietly, phone in hand. When my turn came, I felt a familiar, faint resignation—the knowledge that every haircut now is also a subtraction, a reminder that abundance does not last forever.

Still, we were all there.

That, I realised, was the quiet significance of the morning. Despite technology, convenience, and perfectly serviceable mirrors at home, we had chosen—without discussion—to step out into the cold and submit ourselves to the same old ritual. Not because it was strictly necessary, but because it felt right. Because sitting briefly in another’s care, and emerging altered—however slightly—still carries meaning.

As we stepped back outside, four freshly trimmed heads meeting the same winter air, it occurred to me that civilisation does not endure only through grand ideals or solemn declarations. Sometimes it survives in small, repeated gestures—in showing up, in maintaining appearances not merely for the mirror, but for the world. The haircut, it seems, has never really been about hair alone. It is about continuity.

Whether it will persist forever, I cannot say. But that morning, in Millburn, it was very much alive, passed, once again, from one generation to the next.

(Uday Kumar Varma is an IAS officer. Retired as Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting)

.jpg)

Uday Kumar Varma

Uday Kumar Varma

Related Items

Aloe vera: A magical ingredient for skin and hair