“India dazzled the world in 2025 with growth and ambition—but beneath the headlines lay suspicion, subdued institutions, and justice turned negotiable. As 2026 dawns, will democracy reclaim its balance, or will centralisation harden into permanence?”

Foreword: India at the Crossroads

The year 2025 will be remembered as a paradoxical chapter in India’s journey. On the surface, the nation dazzled with economic dynamism, ambitious reforms, and a confident global voice. Yet beneath the headlines lay troubling signs of democratic erosion, centralisation of authority, and a social fabric increasingly defined by suspicion. Institutions that once stood as guardians of the republic—the judiciary, the media, civil society—appeared subdued, while legislation often resembled rebranding rather than genuine reform. The conditioning of minds, through surveillance, polarisation, and securitisation, became a quiet but pervasive reality.

As India steps into 2026, it finds itself at a critical juncture. The question is not merely whether growth will continue or diplomacy will flourish, but whether the republic can restore balance to its democratic pillars. Will the state reaffirm the citizen’s rights, or will negotiated justice and executive convenience become permanent features of governance? This series of essays is both a retrospective on a tumultuous year and a warning for the path ahead.

1. Legislation: From Rights to Rebranding

Legislation has always been a contested arena in India, but the year 2025 marked a decisive departure in both tone and substance. Parliament, once a forum for deliberation and scrutiny, increasingly resembled a theatre of speed, where sweeping bills were introduced and passed with remarkable haste. The most striking example of this trend was the replacement of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) with the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin), popularly abbreviated as the VB–G RAM G Bill. This change, presented as modernisation, has raised profound questions about the future of rights based governance in India.

To appreciate the significance of this shift, one must recall the extraordinary nature of MNREGA. Enacted in 2005, it was celebrated as the world’s largest rights based employment programme. Its genius lay in transforming a policy aspiration into a legal entitlement. Every rural household was guaranteed one hundred days of wage employment, and the scheme was demand driven: citizens could claim work as a matter of right, and if the state failed to provide it within fifteen days, compensation was legally mandated. This distinguished MNREGA from most international welfare schemes, which are supply driven and capped by budgets. As commentators noted at the time, MNREGA was not charity but a right enforceable in law, a rare example of the state binding itself to the citizen.

The VB–G RAM G Bill, introduced in late 2025, was framed by the government as a bold step towards efficiency and transparency. On paper, it appeared generous, increasing the guaranteed workdays from one hundred to one hundred and twenty five. It promised to reduce leakages through advanced digital monitoring and sought to align rural work projects with national infrastructure priorities. Supporters argued that this represented a necessary evolution, ensuring that public funds created durable assets rather than temporary relief.

Yet beneath the surface, the reality is more complex. Critics and labour unions contend that the bill represents a retreat from the rights based framework that made MNREGA unique. By shifting to a model perceived as supply driven, the government has effectively capped its moral and legal obligation to the poor within the limits of its annual budget. The removal of Mahatma Gandhi’s name from the legislation was seen by many as symbolic erasure, undermining the moral foundation of India’s welfare state. What was once a universal entitlement is now reframed as a programme contingent on fiscal discretion.

The fiscal restructuring of the scheme has further sharpened concerns. Under MNREGA, states were required to contribute only ten per cent of the costs, with the central government bearing the rest. Under the VB–G RAM G Mission, states must now shoulder forty per cent. For poorer states, where demand for rural work is highest, this represents an unsustainable burden. Experts warn that this could lead to exclusion of the most vulnerable citizens from the safety net, precisely those who need it most. Oxfam, in a 2025 report, described India’s retreat from demand driven employment rights as a significant departure from global best practice in inclusive welfare.

Equally troubling was the manner in which the bill was passed. The process drew sharp parallels with the 2020 Farmers’ Laws, which were rammed through Parliament without meaningful consultation. Those reforms provoked a year long protest that eventually forced a rare government retreat in 2021. The VB–G RAM G Bill risks similar unrest if rural livelihoods are perceived to be under threat. This pattern of centralised decision making may be efficient for the executive, but it erodes the consensus building mechanisms vital for the stability of a diverse republic.

The implications of this legislative shift extend beyond the number of workdays guaranteed. At stake is the very nature of the relationship between citizen and state. MNREGA embodied a radical idea: that the poorest citizen could demand work as a matter of right, and the state was legally bound to respond. The VB–G RAM G Bill reframes this relationship, placing the citizen in a more dependent position, reliant on the state’s fiscal priorities rather than empowered by law.

As India looks ahead to 2026, the VB–G RAM G Bill stands as a litmus test. If the government can deliver on its promises of efficiency, transparency, and durable infrastructure without diluting the individual’s right to work, it may yet be remembered as a landmark reform. But if the transition results in bureaucratic delays, exclusion of the poor, or financial strangulation of the states, it could spark significant social and political upheaval.

The deeper question is whether legislation in India will continue to be an exercise in top down rebranding or whether it can return to being a collaborative process that empowers the most vulnerable. The answer will determine whether the vision of “Viksit Bharat” is built on a foundation of genuine inclusive rights or on the shifting sands of executive convenience.

2. Political Climate: Centralisation and the Normalisation of Corruption

The political atmosphere of India in 2025 was defined by an extraordinary consolidation of executive authority, reshaping the traditional understanding of governance. While the ruling establishment celebrated this as stability and decisive leadership, the reality suggested a systematic hollowing out of deliberative processes. Parliament, once the vibrant heart of the world’s largest democracy, increasingly functioned as a stage for speed rather than scrutiny. Significant legislative changes, affecting millions of lives, were frequently passed through voice votes with minimal debate, often while large sections of the opposition were suspended or marginalised. This efficiency was lauded by some as evidence of strong governance, yet constitutional scholars warned that it represented a dangerous erosion of the checks and balances designed to prevent executive overreach.

Accompanying this centralisation was a phenomenon many observers described as the normalisation of corruption. In earlier decades, high level scandals—whether involving defence deals or spectrum allocations—had the power to shake governments and ignite mass outrage. In 2025, however, corruption seemed to have been domesticated. Scandals involving the proximity of top tier politicians to powerful corporate houses, or the opaque funding of political campaigns, were met not with indignation but with weary inevitability. This was not due to a lack of evidence but rather a conditioning of the public mind to accept that the wheels of power required such lubrication. The narrative shifted from “is there corruption?” to “whose corruption is more beneficial to national growth?”—a cynical trade off that threatened the moral fabric of public service.

A particularly distinctive feature of the 2025 political landscape was the overt influence of babas and self styled godmen. These figures, wielding immense social and financial capital, became key arbiters of political legitimacy. Their ashrams often served as parallel centres of power, where ministers and high ranking officials sought blessings in exchange for policy concessions or protection from legal scrutiny. This blurring of the lines between spiritual authority and temporal power created a unique form of negotiated governance, where the rule of law was frequently secondary to the interests of powerful religious lobbies.

The role of investigative agencies further illustrated the fragility of institutional independence. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the Enforcement Directorate (ED) became lightning rods of political contention. Throughout 2025, these agencies displayed what critics called selective zeal. Opposition leaders faced a barrage of raids, summons, and property attachments, while those who defected to the ruling coalition often found their legal troubles miraculously vanishing. This phenomenon, colloquially referred to as the “political washing machine,” fundamentally altered the competitive nature of Indian politics. Dissent became a high risk endeavour, while political loyalty increasingly functioned as a form of legal immunity.

The cumulative effect of these developments was a political culture in which centralisation offered the illusion of order but simultaneously created a single point of failure. Without the corrective mechanisms of a robust opposition and an independent Parliament, the system risked becoming brittle. The normalisation of corruption, meanwhile, eroded the moral foundations of governance, replacing accountability with transactional legitimacy. The influence of godmen blurred the secular character of the state, while the weaponisation of investigative agencies undermined the principle of equality before the law.

As India looks towards 2026, the primary question is whether the electorate will continue to accept this new normal or whether a tipping point will be reached. Centralisation may deliver speed, but democracy requires deliberation. Corruption may be rationalised as inevitable, but its acceptance corrodes trust in institutions. Spiritual authority may provide political cover, but it weakens the secular foundations of governance. And investigative agencies may serve as instruments of executive will, but their selective application of justice undermines the very idea of fairness.

The challenge for the coming year is therefore twofold: to restore the dignity of political institutions and to decouple the pursuit of power from the protection of criminality. India’s democratic experiment has always thrived on diversity, debate, and dissent. If these qualities are subdued in the name of efficiency, the republic risks losing its resilience. The consolidation of authority may appear to strengthen the executive, but without the balancing force of independent institutions, it leaves the system vulnerable to collapse.

Ultimately, the political climate of 2025 serves as a warning. A democracy cannot survive on centralisation alone, nor can it endure if corruption is accepted as the price of progress. The test for 2026 will be whether India can reclaim the spirit of deliberation, restore institutional independence, and reaffirm the principle that power must serve the people rather than protect itself.

3. Social Climate: The Conditioning of Minds

The social fabric of India in 2025 underwent a transformation that was both quiet and profound, reshaping the everyday experience of citizenship. What had long been celebrated as a vibrant and chaotic public life—festivals, gatherings, and spontaneous communal joy—was increasingly shadowed by suspicion and securitisation. The year revealed how deeply the conditioning of minds had taken hold, teaching citizens to view their neighbours with caution and the state with a mixture of fear and dependence.

Festivals, once the hallmark of India’s pluralism, became heavily regulated affairs. The sight of police barricades, drone surveillance, and routine frisking at temples, mosques, and public fairs was no longer exceptional but expected. This was not merely a response to security threats; it was a psychological shift. Citizens were trained to accept surveillance as normal, to internalise the idea that joy must be monitored, and to equate community with risk. The transformation of celebration into securitised spectacle marked a subtle but significant erosion of trust.

This climate was exacerbated by the emboldening of fringe elements. Vigilante groups, technically outside the formal structures of government, operated with a perceived sense of impunity. They took it upon themselves to police morality, dietary habits, and inter faith relationships. Throughout 2025, incidents of street justice were captured on social media, yet the state’s response was often delayed or muted. The result was a hierarchy of citizenship: certain groups felt licensed to offend, while others lived in constant vulnerability. The conditioning occurred when ordinary citizens began to self censor, moderating speech and behaviour to avoid attracting the attention of these non state actors. Liberty shrank not through formal decree but through silent adaptation.

Digital spaces played a decisive role in this transformation. Social media platforms, once heralded as engines of democratisation, became in 2025 the primary vehicles of polarisation. Sophisticated troll farms and automated bots amplified divisive narratives, turning local disputes into national ideological battles. Independent voices—journalists, activists, and academics—who attempted to document the erosion of communal harmony were met with coordinated harassment and doxing. The digital environment created echo chambers in which truth was defined less by evidence than by political affiliation. The conditioning of minds was reinforced by algorithms that rewarded outrage and punished nuance.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the year was the erosion of trust in institutions that traditionally held communities together. Local residents’ associations, academic institutions, and civic organisations increasingly aligned themselves with majoritarian narratives. Universities, once crucibles of dissent and critical thought, faced mounting pressure to conform to the ideological goals of the state. Curricula were reshaped, campus activities monitored, and student movements curtailed. The pluralist spirit that had long defined India’s intellectual life was replaced by rigid adherence to prescribed narratives.

The cumulative effect of these developments was a society in which suspicion became the default mode of interaction. Citizens were conditioned to believe that surveillance was protection, that silence was safety, and that conformity was the price of stability. The conditioning of minds was not imposed through overt coercion alone but through the gradual normalisation of fear and self censorship.

As India enters 2026, the challenge is to reclaim the middle ground. The silent majority must find the courage to reject the politics of dread and restore the everyday secularism that has historically been India’s greatest strength. Without a renewal of social trust, the nation’s economic and political ambitions will remain built on sand. Growth figures and diplomatic achievements cannot compensate for a society where suspicion erodes solidarity and fear replaces fraternity.

The conditioning of minds in 2025 was a reminder that democracy is not only about institutions and elections but also about the daily practice of trust and pluralism. The test for the coming year will be whether India can resist the temptation to accept suspicion as permanent and instead rediscover the confidence to live openly, joyfully, and together.

4.Economic Trajectory: Headline Growth vs. Structural Fragility

India’s economic narrative in 2025 was a study in striking contradictions. On the global stage, the country was hailed as a bright spot in an otherwise sluggish world economy, officially becoming the world’s fourth largest economy. Headline GDP growth remained resilient at 6.5 per cent, and the government’s “Viksit Bharat” vision was backed by record breaking capital expenditure on infrastructure. High speed railways, sprawling expressways, and state of the art airports symbolised the ambition of a nation determined to project itself as a modern powerhouse. Digital transformation reached its zenith, with the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) processing billions of transactions each month, placing India at the forefront of the global fintech revolution.

Yet beneath these glittering headlines lay deep structural fragilities that raised questions about the sustainability of this growth. The most immediate concern was the performance of the Indian rupee, which ended the year as Asia’s worst performing currency. Sliding towards the ninety mark against the US dollar, the rupee’s weakness reflected significant capital outflows and a widening trade deficit. Investor confidence was further shaken by a scathing assessment from the International Monetary Fund, which awarded India’s national accounts a “C” grade for data quality. The IMF noted that outdated methodologies and opaque data collection hampered global surveillance and made it difficult to gauge the true health of the economy.

This “data gap” masked a growing divide between the India that consumes and the India that toils. Urban luxury markets and high end services thrived, with malls and digital platforms catering to a burgeoning middle class. Yet rural distress remained acute. The transition from MNREGA to the VB–G RAM G Bill created uncertainty for millions of households who had relied on guaranteed employment as a safety net. Youth unemployment, particularly among the educated, remained stubbornly high, fuelling resentment and contributing to a quiet but steady brain drain. The much promised $5 trillion economy target, once set for 2024, was quietly pushed back to 2028–29, an admission that the demographic dividend risked becoming a demographic disaster.

Crony capitalism cast a long shadow over the economic landscape. Wealth became increasingly concentrated in a handful of conglomerates, celebrated as “national champions” but criticised for their dominance. These entities were instrumental in building infrastructure and driving investment, yet their growing influence raised concerns about market competition and the risk of oligarchy. The banking sector, already fragile, faced exposure to these giants, creating a “too big to fail” dilemma reminiscent of the Gilded Age. The normalisation of corruption in the political sphere found its economic counterpart in negotiated contracts and regulatory environments tailored to favour specific players.

The fragility of India’s growth model was further exposed by its dependence on external conditions. Global interest rates remained high, trade alliances shifted, and geopolitical tensions added volatility to supply chains. India’s export competitiveness was undermined by protectionist policies abroad, while domestic inflation eroded purchasing power. The paradox was stark: India was celebrated internationally for its growth figures, yet domestically many citizens felt excluded from its benefits.

Looking ahead to 2026, the economic imperative is clear. India must move beyond headline management and address structural flaws. Transparent data practices are essential to restore credibility. Rural revitalisation must become more than rhetoric, with genuine investment in agriculture, employment, and social infrastructure. Youth unemployment requires urgent attention, not only to prevent disillusionment but to harness the potential of a generation that could otherwise be lost. Regulatory frameworks must encourage broad based entrepreneurship rather than entrench oligarchical control.

The global environment will leave little room for error. Trade disputes, currency volatility, and climate pressures will test India’s resilience. The country’s status as an economic powerhouse will ultimately depend not on its ability to produce optimistic statistics but on its capacity to create jobs, stability, and opportunity for the 1.4 billion people behind those numbers.

The economic story of 2025 is therefore not one of triumph alone but of warning. India has demonstrated its capacity for growth, ambition, and innovation. Yet unless structural fragilities are addressed, the glittering headlines risk becoming hollow. The challenge for 2026 is to ensure that the promise of Viksit Bharat rests on solid foundations rather than shifting sands.

5.Diplomacy: Global Ambition and Domestic Vulnerability

India’s diplomatic posture in 2025 was marked by ambition and paradox. On the one hand, the country sought to position itself as the “Vishwa Mitra”—the global friend—an indispensable power capable of bridging divides between the Global North and the Global South. On the other, its aspirations were frequently undermined by domestic fragility and bilateral disputes that exposed the limits of its strategic autonomy.

India’s voice was louder than ever in international forums. At the G20, BRICS+, and other multilateral platforms, New Delhi advocated reform of the United Nations Security Council, pressing for a permanent seat to reflect contemporary realities. It positioned itself as a strategic counterweight to China’s expanding influence in the Indo Pacific, while simultaneously deepening ties with Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia. The government’s rhetoric emphasised “assertive neutrality,” refusing to be pigeonholed into Cold War style blocs and instead presenting India as a mediator between competing powers. This ambition reflected a desire to be seen not merely as a regional actor but as a global leader.

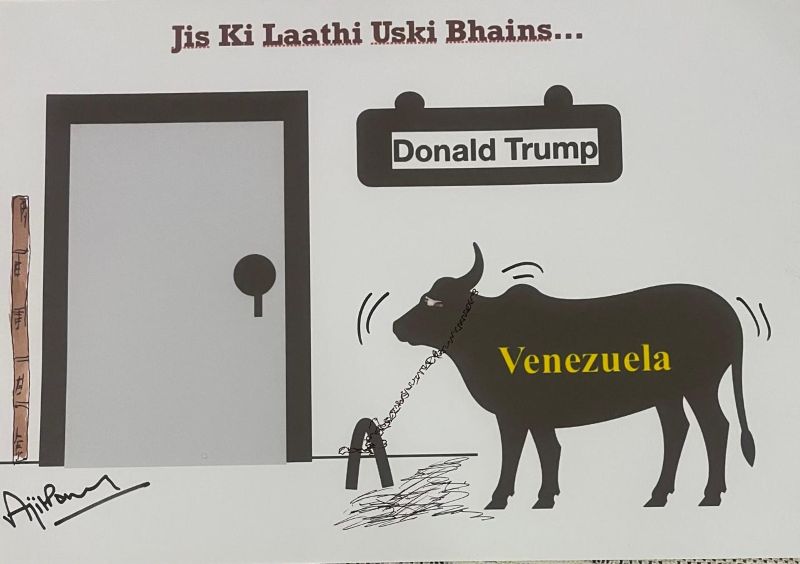

Yet this global ambition was repeatedly tested by vulnerabilities closer to home. The most significant challenge came from an unexpected quarter: a deepening trade dispute with the United States. Despite strategic alignment on security, the economic partnership faltered. Washington, citing India’s protectionist barriers and high duties on American goods, imposed reciprocal tariffs of up to fifty per cent on key Indian exports, including steel, aluminium, and pharmaceutical components. This tariff war revealed the fragility of the Indo US relationship, demonstrating that shared democratic values are no guarantee against economic conflict. For India, the dispute was a sobering reminder that global friendship requires more than rhetoric; it demands the resolution of hard economic realities.

Relations with China remained locked in a state of armed stalemate. Diplomatic channels remained open, but disengagement along the Line of Actual Control stalled. A significant portion of India’s military and financial resources continued to be tied to its northern borders, limiting its ability to project power elsewhere. Meanwhile, China’s Belt and Road Initiative advanced in India’s immediate neighbourhood, making inroads in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. New Delhi was forced into a costly and reactive posture, attempting to counter Chinese influence with hurried investments and diplomatic overtures. The persistence of border tensions underscored the limits of India’s strategic autonomy: it is difficult to act as a global mediator when one’s own borders remain contested.

India’s climate diplomacy in 2025 was equally paradoxical. At COP30, New Delhi made bold pledges on renewable energy capacity and green hydrogen production, positioning itself as a leader in the global energy transition. Yet the domestic reality told a different story. Coal dependency remained high, air quality in major cities worsened, and environmental regulations were implemented slowly. International observers criticised the gap between rhetoric and reality, arguing that the pursuit of GDP growth was being prioritised over ecological sustainability. For India, this contradiction risked undermining its credibility as a climate leader, exposing the tension between economic ambition and environmental responsibility.

The cumulative effect of these vulnerabilities was to temper India’s global ambition with caution. The country’s diplomatic strategy in 2025 was ambitious in scope but inconsistent in execution. Assertive neutrality allowed India to avoid entanglement in rigid blocs, but it also risked leaving the country isolated when disputes arose. Trade frictions with the United States, border tensions with China, and climate contradictions all revealed that ambition alone is insufficient.

As 2026 approaches, Indian diplomacy faces a litmus test of reliability. The era of being “everything to everyone” may be drawing to a close. To secure its place as a global power, India must resolve its trade disputes with the West, find a sustainable modus vivendi with China, and ensure that domestic actions align with international commitments. Ambition is a necessary starting point, but consistency is the currency of true leadership.

India’s diplomatic story in 2025 is therefore one of paradox: a nation eager to be seen as indispensable, yet constrained by vulnerabilities that undermine its credibility. The challenge for 2026 is to transform ambition into reliability, rhetoric into reality, and aspiration into achievement. Only then can India’s claim to global leadership rest on solid ground.

6.Democracy and Institutions: Subdued Guardians

If 2025 was the year of executive dominance, it was equally the year of institutional fatigue. The pillars of India’s democracy—the judiciary, the Election Commission, the media, and civil society—remained formally intact but appeared increasingly subdued. Their ability to act as independent guardians of the republic was compromised not by sudden collapse but by gradual subjugation, achieved through executive pressure, strategic appointments, and the co option of leadership.

The judiciary, traditionally the last line of defence for constitutional rights, found itself in a deferential position relative to the state. While the higher courts occasionally delivered brave judgements on minor issues, they were perceived as reluctant to challenge the government on core constitutional matters. Cases involving surveillance powers, controversial land acquisitions, and fundamental rights were delayed, sometimes indefinitely. The maxim “justice delayed is justice denied” acquired renewed force, particularly for political dissenters held under stringent anti terror laws. The judicial retreat of 2025 was not marked by dramatic capitulation but by a quiet reluctance to confront the executive on matters of principle.

The media landscape revealed a parallel erosion. The normalisation of corruption in politics found its counterpart in the normalisation of propaganda. Many of the country’s largest media houses were owned by corporate conglomerates with deep ties to the ruling establishment. The line between journalism and state communication blurred, as prime time debates increasingly echoed government narratives. Independent journalists and small, digital first outlets attempted to fill the void, but they were hamstrung by restrictive IT rules and the constant threat of legal harassment. Strategic lawsuits against public participation—SLAPP suits—became a favoured tool to silence dissent. The result was an information ecosystem where the state’s narrative was amplified, while dissenting facts were drowned out by manufactured outrage.

Civil society faced similar pressures. Expansive new surveillance and data laws were introduced under the guise of national security and digital economy. These laws gave the executive unprecedented powers to intercept communications and access personal data with minimal judicial oversight. Activists, academics, and NGOs found their funding squeezed and their activities monitored. The chilling effect was palpable: the awareness that one’s digital footprint was always under scrutiny discouraged open debate and curtailed civic engagement. The subjugation of the mind began not with overt censorship but with the quiet knowledge that surveillance was constant.

Yet 2025 also demonstrated that the spirit of democracy is not easily extinguished. Small but persistent pockets of resistance continued to challenge the narrative of inevitability. Student movements, grassroots environmental groups, and local campaigns against land acquisitions provided reminders that dissent, though marginalised, remained alive. These islands of dissent were fragile, but they carried symbolic weight. They represented the enduring belief that democracy is more than the act of voting every five years; it is the daily functioning of independent institutions that hold power to account.

The cumulative effect of institutional fatigue was a republic that appeared outwardly stable but inwardly brittle. The judiciary’s reluctance to confront the executive weakened constitutional safeguards. The media’s drift into propaganda eroded the public sphere. Civil society’s surveillance induced silence curtailed pluralism. Together, these trends created a democracy that functioned procedurally but faltered substantively.

As India enters 2026, the challenge is to restore the teeth of these guardians before they become mere ornaments of the state. The judiciary must reclaim its role as an impartial arbiter of rights, delivering timely judgements on matters of constitutional importance. The media must rediscover its vocation as a watchdog rather than a megaphone. Civil society must be allowed to operate without fear of surveillance or financial strangulation. Without such renewal, democracy risks becoming hollow, reduced to ritual rather than substance.

The story of 2025 is therefore not only about executive dominance but about the quiet weakening of institutions that once defined India’s democratic resilience. The test for 2026 will be whether these subdued guardians can recover their independence and restore balance to the republic. For democracy is not sustained by slogans or ceremonies but by institutions that act daily to hold power accountable.

7.Normalisation of Criminality: Justice Negotiated

Perhaps the most distressing development of 2025 was the creeping normalisation of criminality within India’s political and legal systems. What had once been dismissed as inefficiency or delay in the delivery of justice evolved into something more corrosive: negotiated justice, where the application of law appeared contingent on the identity, influence, or political utility of the accused. The year revealed a disturbing pattern in which criminality was not only tolerated but, in some cases, celebrated, eroding the very foundations of the rule of law.

High profile cases involving heinous crimes became sites of political theatre rather than arenas of accountability. The selective use of remissions and the withdrawal of criminal cases stood out as defining features of the year. The early release of convicts in cases that had previously shocked the national conscience—such as the Bilkis Bano case—and the handling of the Sengar case sent a chilling message: justice was no longer absolute but subject to negotiation. When those convicted of grave crimes were greeted with garlands and public celebrations by political affiliates, it signalled a fundamental breakdown in the moral authority of the state. Criminality was reframed not as a violation of law but as a fluid concept, easily washed away by the laundry of political patronage.

This normalisation extended to the state’s handling of fringe violence. Lynchings and vigilante actions, often carried out in the name of protecting tradition or national interest, were met with delayed prosecutions or the quiet withdrawal of charges. The effect was the creation of a climate of legalised lawlessness, where certain individuals felt they were more equal than others before the law. Victims were left with the impression that justice was a luxury, available only when their plight did not clash with dominant political narratives.

The police, the most immediate interface between citizen and law, increasingly appeared as an instrument of executive will rather than an independent enforcer of justice. The rise of “bulldozer justice”—the extra judicial demolition of homes belonging to those accused, but not convicted, of crimes—became a popular spectacle. This bypassing of courts catered to a public hunger for instant justice, but it simultaneously eroded the principle of innocence until proven guilty. Punishment was transformed into performance, designed to project strength rather than uphold fairness.

The cumulative effect of these practices was a society in which justice became negotiable. The law was no longer perceived as an impartial arbiter but as a tool wielded selectively, rewarding loyalty and punishing dissent. This undermined the very notion of equality before the law, replacing it with a hierarchy of impunity. The conditioning of minds, already evident in the social sphere, extended into the legal domain: citizens began to accept that justice was contingent, that the powerful could bend rules, and that accountability was optional.

As India looks towards 2026, the normalisation of criminality stands as perhaps the greatest threat to internal stability. A society where justice is negotiated is a society where nobody is truly safe. The erosion of impartiality in law enforcement and the judiciary risks creating a permanent state of insecurity, where citizens cannot rely on institutions to protect them. The spectacle of bulldozer justice may satisfy immediate demands for order, but it corrodes the long term legitimacy of the legal system.

The litmus test for the coming year will be whether the judiciary and the police can reclaim their roles as impartial guardians of justice. Restoring the principle that the law is above all, no matter how powerful the individual, is not merely a moral imperative but a practical necessity for a nation that aspires to be a modern, developed power. Without a return to the absolute rule of law, the vision of Viksit Bharat risks becoming an empty slogan, shadowed by the ghost of injustice.

The story of 2025 is therefore not only about political centralisation or economic paradox but about the corrosion of justice itself. If criminality continues to be normalised, India risks undermining the very foundation of its democracy. The challenge for 2026 is to reverse this trend, to reaffirm that justice is not negotiable, and to ensure that the law serves as a shield for the vulnerable rather than a weapon for the powerful.

Epilogue: The Road Beyond 2026

India’s story at the close of 2025 is one of paradox, ambition, and warning. The essays in this series have traced how centralisation delivered speed but eroded deliberation, how corruption was normalised, how suspicion conditioned society, and how economic growth concealed fragility. They have shown how diplomacy sought global leadership yet faltered on domestic contradictions, how institutions became subdued, and how justice itself was negotiated.

The road to 2026 is therefore not simply a continuation but a crossroads. One path leads towards deeper centralisation, where rights are diluted, institutions weakened, and justice remains contingent. The other path demands renewal: of trust, of pluralism, of the rule of law. The choice will determine whether India’s vision of “Viksit Bharat” rests on solid foundations or collapses under the weight of its contradictions.

The epilogue is not a conclusion but an invitation. It calls upon citizens, institutions, and leaders to recognise that democracy is not sustained by statistics or slogans but by the courage to uphold fairness, inclusion, and accountability. India’s greatness has always lain in its ability to reconcile diversity with unity, ambition with restraint, and power with responsibility. The test of 2026 will be whether that balance can be restored.

Author’s Note

This series was written to provoke reflection on the paradoxes of India in 2025. It is neither a celebration nor a lament, but an attempt to capture the contradictions of a nation where ambition often collided with erosion, and reform was too frequently reduced to renaming. The essays trace how legislation shifted from rights to rebranding, how political centralisation bred corruption and selective justice, how suspicion conditioned social life, and how economic headlines concealed fragility. They explore India’s global ambition, its subdued institutions, and the disturbing normalisation of criminality.

My intent is not to offer easy answers but to raise urgent questions. Can democracy survive on centralisation alone? Can economic growth be sustained without transparency and inclusion? Can diplomacy thrive when domestic vulnerabilities remain unresolved? Above all, can justice remain negotiable without corroding the foundations of the republic?

As India enters 2026, the challenge is to resist the temptation of complacency. The resilience of democracy lies not in slogans or ceremonies but in the daily functioning of institutions, the courage of dissent, and the restoration of trust. This series is offered as both record and reminder: that the path chosen now will shape not only the year ahead but the moral trajectory of the nation.

(Views are personal)

(The writer is a retired officer of the Indian Information Service and a former Editor-in-Charge of DD News and AIR News (Akashvani), India’s national broadcasters. I have also served as an international media consultant with UNICEF Nigeria and been contributing regularly to various publications)

<><><>

.jpg)

Krishan Gopal Sharma

Krishan Gopal Sharma

Related Items

Not accurate: India after Trump aide's remarks on trade deal

Modi didn't call, Trump aide explains why India-US trade deal derailed

India to launch cashless treatment for victims of road accidents