Part 1: Rise, Dominance, and the Recent Crisis

India’s skies have never been busier. Domestic aviation has grown explosively over the past two decades, carrying millions of passengers who would once have regarded air travel as a luxury. Low-cost carriers like IndiGo and SpiceJet have democratized flying, making it accessible even to aspirational lowermiddle- class families, while full-service carriers such as Air India and Vistara cater to premium travellers. Yet beneath this expansion lies a paradox: growth has often outpaced stability, leaving the sector exposed to crises that ripple far beyond any single airline.

This fragility was starkly illustrated in early December when IndiGo, India’s largest domestic airline, cancelled more than half of its roughly 2,300 daily flights. Tens of thousands of passengers were stranded. Delhi, the country’s busiest airport, effectively shut down for domestic departures. Weddings were attended via video call; business trips collapsed into chaos. What would have been a serious operational failure in other markets became a national disruption, revealing how deeply the country’s air travel system depends on a single carrier.

IndiGo’s meltdown was operational in origin: new regulations increasing pilots’ mandatory rest periods were implemented last month, and the airline’s famously tight schedules lacked sufficient buffers. Minor disruptions cascaded into system-wide cancellations. Yet the crisis also exposed structural vulnerabilities that go far beyond operational mismanagement.

The Indian domestic market is heavily concentrated. IndiGo commands roughly two-thirds of domestic passengers and operates as the sole carrier on a majority of routes. Air India, despite its legacy and recent privatization, holds only about 27% of the market and faces its own operational constraints, including delayed aircraft deliveries and lingering safety challenges. By comparison, no airline in the United States or Europe controls such a dominant share of domestic traffic. In mature markets, when one carrier falters, others absorb the slack. In India, such redundancy is minimal, turning individual operational glitches into systemic crises.

Underlying this fragility are policy and regulatory realities that make profitability exceedingly difficult. Aviation turbine fuel (ATF) taxes are among the highest in the world, consuming roughly 40–45% of an airline’s operational costs. Airport charges, both in public and private terminals, further inflate costs. Airlines earn revenue in a highly price-sensitive market, where even marginal fare increases trigger scrutiny or public outcry. Schemes such as UDAN, designed to make air travel affordable in smaller towns, impose fare caps that often render routes financially unsustainable. Legacy rules like the “5/20” requirement—forcing new carriers to own 20 aircraft and operate for five years before flying internationally—shield incumbents while delaying meaningful competition.

History confirms the consequences. Kingfisher Airlines collapsed spectacularly. Jet Airways bled out despite a strong market presence. Go First faltered in its early years. SpiceJet oscillates between profit and loss. Only IndiGo has consistently remained profitable—an outcome less of systemic health than of Darwinian survival under harsh conditions.

India’s infrastructure story adds another layer of complexity. Airports have expanded dramatically, yet many remain underutilized. Ghost airports in smaller towns illustrate the perils of expansion divorced from operational sustainability. Without viable airline operations to populate these airports,investments fail to generate economic benefits, leaving both carriers and the government with stranded capital. Rail and road networks, though improved, cannot absorb sudden aviation shocks, underscoring the importance of robust, reliable air services.

The December crisis, while extreme, is symptomatic of a deeper malaise. Growth has occurred without stability; scale has been achieved without redundancy; efficiency has been pursued without resilience. India’s aviation sector, vibrant and aspirational as it is, remains perilously dependent on the operational health of a single airline. Passengers benefit from wider access and competitive fares, yet even small operational or regulatory shocks can trigger disproportionate disruption.

Part 2: Profitability, Policy, and the Road Ahead

If Part 1 traced the dramatic growth and fragility of Indian aviation, Part 2 examines why profitability remains elusive, the structural and regulatory bottlenecks that reinforce fragility, and what can realistically be done to secure the sector’s future.

Despite soaring passenger numbers, airlines struggle to convert traffic into profits. Fuel is the largest single cost: ATF taxes in India are among the world’s highest, sometimes exceeding 30–35% of ticket revenue. Airport charges further inflate costs. Indian passengers are extremely price-sensitive, and fare caps under schemes like UDAN often render routes financially unsustainable. Ancillary revenues—cargo, business-class premiums, lounges—remain limited compared to global peers. As a result, passenger growth alone does not ensure financial stability.

Historical patterns confirm this paradox. Legacy carriers like Jet Airways and Go First collapsed; SpiceJet has oscillated between losses and recovery for years. IndiGo remains profitable, but its dominance leaves the sector structurally fragile. Minimal redundancy means that if the largest carrier falters, the system experiences cascading failures, as the December crisis demonstrated.

Regulatory complexity compounds these challenges. Rules like the “5/20” requirement and Route Dispersal Guidelines, combined with micromanagement by regulators, create uncertainty. Even fare adjustments are fraught: airlines face scrutiny for raising prices, while fuel taxes and airport fees can spike without warning. The result is a market that is deregulated in theory but tightly constrained in practice.

Short-term challenges for new entrants, recently licensed by the government, are formidable. Airlines require years to reach operational maturity: aircraft procurement, crew training, route allocation, and airport slots all demand careful planning and substantial capital. Without predictable taxation and regulatory clarity, new carriers risk joining the growing list of airline failures before achieving scale.

Infrastructure constraints remain significant. Dozens of underutilized airports highlight the disconnect between infrastructure expansion and operational sustainability. Without financially viable airlines, even newly built airports cannot stimulate local economies. Alternative transport modes—railways and roads—cannot absorb sudden aviation disruptions, further emphasizing the importance of resilient air services.

Addressing these challenges requires both short-term and medium-term strategies. In the near term, rationalizing ATF taxes and airport fees would reduce immediate cost pressures. Streamlining regulations—simplifying route dispersal obligations, clarifying fare policies, and reducing unpredictable interventions—would enhance operational confidence. Support for new entrants, such as targeted capital or temporary incentives, could help them survive initial years while building operational scale.

Medium-term reforms must focus on resilience and competition. Encouraging multiple carriers on the same routes, fostering financially sustainable low-cost carriers, and enabling market-based pricing are critical. Policy must recognize that aviation is strategic infrastructure: stable airlines enhance connectivity, commerce, and national growth. Lessons from Singapore or Dubai show that treating aviation as a national instrument—rather than merely a revenue source—yields long-term benefits.

The prognosis is cautiously optimistic. India’s domestic air travel will likely continue its upward trajectory, driven by rising incomes, urbanization, and consumer aspiration. Yet without structural reforms, policy clarity, and financial prudence, crises like the IndiGo meltdown may recur. New entrants will face the same pressures as their predecessors unless the economics of Indian aviation are corrected.

Ultimately, India’s aviation sector is at a crossroads. Its infrastructure is impressive, its market large, and its consumer base aspirational. But growth alone is insufficient; stability, competition, and financial viability are essential. Until this balance is struck, India will continue producing passengers in record numbers—and, tragically, state funerals for airlines struggling to survive in skies engineered for fragility.

(Uday Kumar Varma is an IAS officer. Retired as Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting)

.jpg)

Uday Kumar Varma

Uday Kumar Varma

Related Items

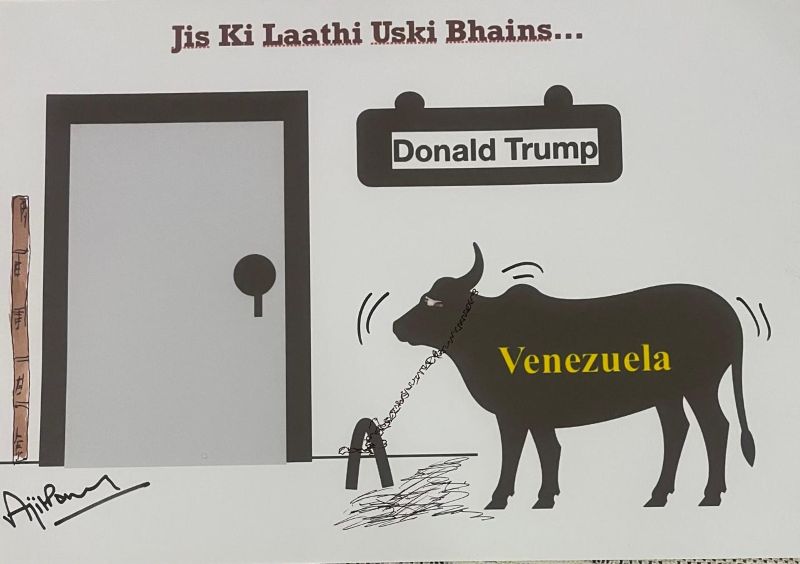

Not accurate: India after Trump aide's remarks on trade deal

Modi didn't call, Trump aide explains why India-US trade deal derailed

India to launch cashless treatment for victims of road accidents