Tea’s story begins, as so many civilizational sagas do, in the folds of myth. Chinese legend places its origin with Emperor Shen Nong in 2737 BCE, when a few wild leaves drifted into his pot of boiling water. Whether accident or providence, the infusion released an aroma so alluring and a taste so delicate that it became, over centuries, less a beverage than a cultural force. Another tale speaks of Bodhidharma, the Buddhist monk who, after falling asleep during meditation, plucked off his eyelids in penance; from the soil where they fell, the first tea plants are said to have grown, their leaves keeping future seekers wakeful in their pursuit of enlightenment.

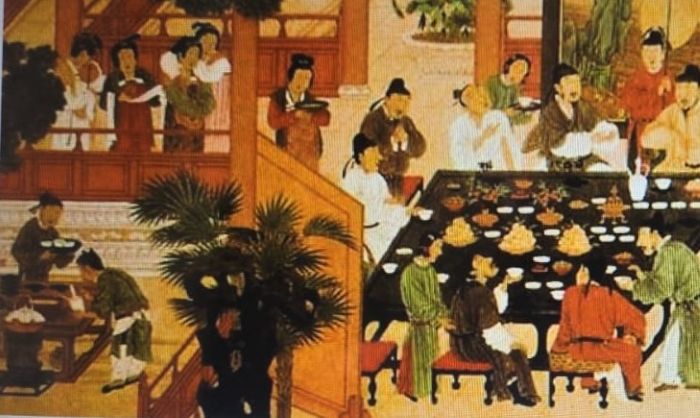

From these mythic beginnings, tea became inseparable from the civilizational rhythms of East Asia. In China, its virtues were extolled in poetry and codified in philosophy. By the Tang dynasty, tea was considered not only nourishment but also a refinement of the soul. Lu Yu’s Cha Jing—the “Classic of Tea,” written in the eighth century—elevated the leaf to near-scriptural status, detailing its cultivation, preparation, and meaning. “Tea,” wrote Lu Yu, “is the taste of harmony,” and indeed harmony was its calling card: harmony between man and nature, host and guest, body and spirit. The Tang poet Lu Tong confessed in verse, “The first bowl moistens my lips and throat; the second shatters my loneliness; the third penetrates my dried entrails, banishing all ignorance.”

Japanese Tea Ceremony

The spread of tea within Asia was itself a cultural symphony. In Japan, tea arrived with Buddhist monks in the early centuries of the first millennium. Over time it became the soul of chanoyu, the Japanese tea ceremony, where every gesture—from the whisking of matcha to the placement of the bowl—was ritualized into an art form. Here, tea was time distilled in a cup, a choreography of simplicity and presence. In Korea, darye—the “etiquette of tea”—wove quiet respect and balance into family and social life. Across East Asia, tea was not mere consumption, but ceremony: an act of discipline, hospitality, and communion with the present moment.

For millennia, the world beyond Asia knew little of this liquid philosophy. Tea’s first tentative journeys westward came along the Silk Road, traded as an exotic curiosity. But its decisive leap occurred in the age of maritime empires. By the seventeenth century, Dutch ships carried it into European ports, and soon it was pouring into English parlours. At first, tea was expensive, a delicacy reserved for the aristocracy, its porcelain cups as prized as the leaves they contained. But its allure was irresistible. Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary in 1660 that he had “drank a cup of tee (a China drink),” marking tea’s hesitant arrival in English daily life. Within decades, it would be indispensable.

The Silk Route

The eighteenth century turned tea into both symbol and battleground. In England, it became a marker of refinement, yet also of taxation and trade monopoly. The East India Company, recognizing both profit and power in its leaves, ensured that tea was not merely a drink but an instrument of empire. India and Ceylon became vast laboratories of monoculture, their hills terraced and regimented, their labourers tethered to the rhythms of the leaf. Across the Atlantic, resistance brewed: the Boston Tea Party of 1773 was not just a protest against taxation, but also an early sign of tea’s strange position as both beloved drink and political pawn. Thomas De Quincey would later call tea “the perfect symbol of insurrection and obedience”—a paradox steeped in every cup.

By the nineteenth century, the triumph of tea was complete. It had travelled further and faster than almost any other commodity of its age. Coffee, wine, and indigenous tonics endured, but none could rival tea’s universality. It was democratic, adaptable, and endlessly elastic—equally at home in the ceremonies of Kyoto, the stalls of Kolkata, and the kettles of Yorkshire. It could be delicate and meditative, strong and sugary, spiced and simmered, or brisk and utilitarian. Few substances have so completely adapted themselves to human taste.

George Orwell, reflecting on the English obsession, declared that tea was “one of the mainstays of civilization,” a comfort against chaos and a ritual of continuity. In truth, the same could be said in Cairo, Calcutta, or Kyoto. In barely two centuries, tea went from being a regional secret to a planetary staple. Its victory was not only commercial but civilizational: it displaced local beverages, reshaped economies, and became, in many ways, the first truly global addiction. If modernity required a drink to soothe its restlessness, sharpen its edge, and bind its communities, tea had already volunteered—and triumphed.

(To Be Continued…….)

(Uday Kumar Varma is an IAS officer. Retired as Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting)

.jpg)

Uday Kumar Varma

Uday Kumar Varma

Related Items

Trump slaps 100 pc tariff on Chinese goods from November 1

Sanae Takaichi set to become Japan’s first female PM

MP Tourism showcases 'Incredible India's Heart' at Paris, Japan expos